|

HARPER'S

|

| Vol.CXII | APRIL, 1906 | No. DCLXXI |

The Blubber HuntersBY CLIFFORD WARREN ASHLEYPICTURES BY THE AUTHORI — FITTING OUT AND CRUISINGWhaling, of all our early industries, has come down to us to-day the least altered in the lapse of years, the least affected by changed conditions, the least trammelled by modern appliances. Of all pursuits, it has preserved to the greatest degree its original picturesqueness.

Modern methods have been applied only to the off-shore fishery; deep-sea whaling, sperm whaling, differs scarcely at all from the whaling of a century ago.

In August of 1904 I shipped from New Bedford on the bark Sunbeam, bound on a sperm-whaling voyage to the west coast of Africa and Crozet Island grounds.

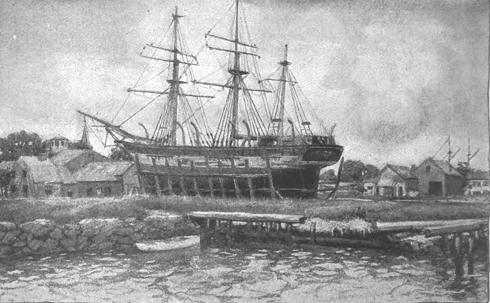

The Sunbeam is a hark of 255 tons, next to the Canton the oldest whaler afloat, launched at Mattapoisett before England had laid the keel of the last of her "wooden walls." When I came to New Bedford in early July the Sunbeam was the only square-rigger being fitted. Battered and weather-beaten she lay at her berth, partially dismantled, a swarm of workers patching and calking her sides.

The next day she was hauled out on the railroad over on the Fairhaven shore. Here her bottom was overhauled and recoppered. Though fifty years old, her keel was straight as a gun-barrel. The Sunbeam's sheathing had not been off in fifteen years. Many of her planks were rotten, and in one place a stone, which had gotten in when she was building, had washed around next her keel and worn through nearly four inches of planking.

In 1854 one hundred and thirteen whalers sailed from New Bedford; fifty years later, five. That which could not |

be effected by the capture of thirty-four vessels by the Shenandoah, the sinking of thirty-nine in the Stone Fleet of Charleston harbor, the abandonment: ... two seasons of fifty-four in the arctic, and other catastrophes no less insinuating if less spectacular, has been accomplished by petroleum. Whaling to-day may be reckoned a dead industry – not that it is extinct, but because it can never recover.

Efforts have been made in vain to induce the government to use sperm-oil in the naval, revenue, and lighthouse services. Such a step, by giving a new impetus to whaling, could scarce fail to be effective in the upbuilding of our naval reserve. New Bedford is still the greatest whaling port in the world, but at best this is an empty title. Where once her fleet numbered hundreds, to-day there are less than thirty.

There was some difficulty attendant on my arrangement for a berth on the Sunbeam; a whaler is often so full-handed that a bunk must be used watch and watch about, and seldom if ever is there a spare one. The owners finally made a place for me in the steerage along with the boat-steerers, and the captain proffered the freedom of his cabin, and suggested that the cooper might be persuaded to set up a bunk for me in his own stateroom after we were under weigh.

I located Cooper in a Water Street grog-shop, and I secured a word with him in private. We seemed to take to each other from the start. He assured me he was the biggest liar in the world, Munchausen alone excepted, hinted darkly of literary efforts of his own, yet to appear, and suggested collaboration. The matter of the berth was easily settled. That same afternoon I signed the ship's papers.

The day before we were to clear, Friday, I put my chest on board. My bunk was made up and the usual calico curtain strung before it.

Saturday brought a gale from the southward, and by noon it was decided to postpone the sailing-till Sunday. The Sunbeam had put into the stream overnight, and was anchored near the Fairhaven shore, with a part of the crew on board.

The owners of the Sunbeam are the oldest firm of ship-owners in the whaling business, having, under the present name and heads, controlled vessels since 1856. The firm's office is in the rear of their clothing and outfitting establishment.

Sunday morning, long before the |

church-bells rang, we were gathering in the darkened front of the store. I had stopped at the post-office for my last mail, and as I stepped out again into the bright sunshine of that August morning, a couple of sailors lumbered hastily by and dodged around the corner. As they were vanishing, one of the "owners" appeared in the street, gazing up and down in a mystified manner, vainly seeking a glimpse of the runaways. When he saw me he hailed cheerfully. From the alley whence he had emerged a series of derisive hoots followed him, then a wagon-load of seamen appeared, being trundled off to the river. Swaying and pitching as the cart jolted over the cobbles, they boisterously spoke each passerby making the street hideous with their yells. Before I entered the store I saw them, one by one, dropping off over the tail-board, utterly oblivious to the protests of the unfortunate dry-goods clerk who was held responsible for their delivery.

The front shop was crowded and noisy, but the real hubbub was in a small back room. Here the sailors, howling and pounding, were locked up when caught, and held till the return of the wagon to take them off to the river. Word was received that the mate refused to go on board till he had partaken of his Sunday dinner. On various pretexts others sought to get off for a while longer – one had forgotten to hid his mother good-by; another had left home without an overcoat. The clerks rushed frantically about. Each man had to be rounded up – not once, but half a dozen times.

The morning dragged out toward noon. A carriage had been sent for the mate; the little back room was emptied. Cooper was sitting on the edge of a black-draped counter, and a clerk was vainly trying to induce him to go on board. Smilingly the cooper doomed the man to eternal perdition; then picturesquely started in to abuse his ancestors. The disgusted clerk gave up the job as thankless; and Cooper sat on, furtively keeping his eye on the ship's chronometer, knowing full well that of all things this would be the last to be taken on board.

We were on the tug, watching the crew tumbling into the pilot-boat, when a commotion at the far end of the wharf attracted our attention, and a clerk hove into view, puffing like a porpoise. dragging behind him by a string one of the boat-steerers. As they drew near we could see that the string was attached to the much-elongated neck of a tan-colored pup. The owner, holding the unlucky mongrel tightly to his breast, struggled to keep up, but the pace was too stiff for him. In a state of complete exhaustion, the three made the sloop just as she was casting off.

We followed the pilot-boat out across the Acushnet to where the Sunbeam lay, redolent in her newly applied paint, spick and span from sprit to taffrail. Under her gallows hung all of a hundred fresh green cabbages, the deck crate was filled with potatoes, and a quarter of beef was suspended from the skids. The hatches were buried completely under a heap of mattresses and baggage. We clambered up the man-ropes, and immediately all |

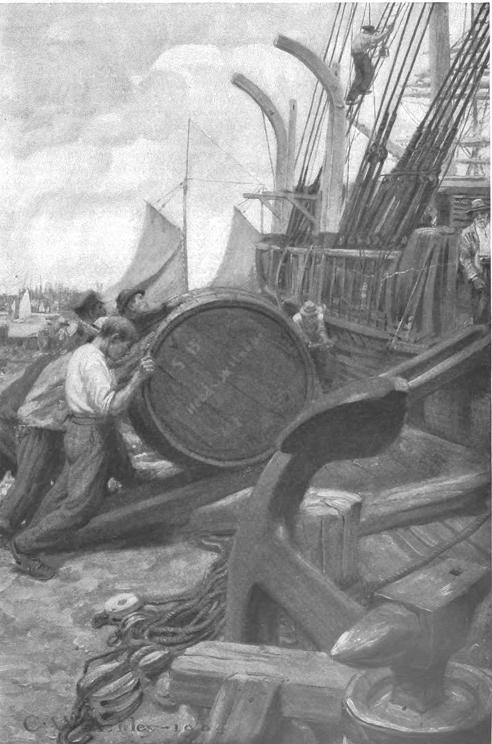

Taking on the Cargo |

was confusion. The green hands, resplendent in new suits of dungaree, were falling over one another in their efforts to execute orders. Without loss of time the hawser was passed from the tug and the command given to weigh anchor. Amid the clicking of pawls and the groaning of the windlass we got under weigh, and on the outgoing tide we were towed down the river. There were over thirty visitors with us for the trip down the bay, friends and relatives of the captain, crew, and owners, who would return to town with the pilot-boat.

We were scarcely abreast of Fort Phoenix when a small naphtha-launch, which had been following us for some time, shot alongside. She carried one passenger – a much-frightened Portuguese in white ducks and a new straw hat, – who, tightly grasping a fiddle in one hand and gesticulating with the other, attempted to explain himself a belated member of our crew desiring to come on board. Even when he had made himself clear, the deal nearly fell through when the question came up as to who should pay his launch lire, and he scrambled up the fore-chains.

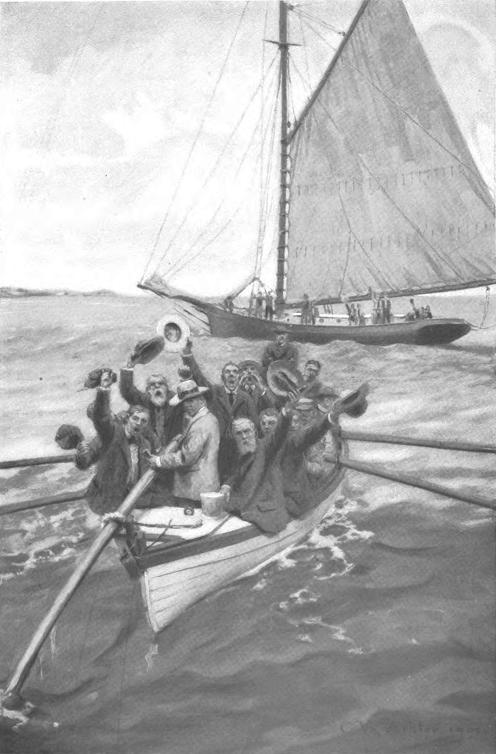

Early in the afternoon a lunch was served to all hands, of cold corned beef and pilot-biscuit. Then the tug left us, and with a creaking of blocks and a hollow flapping the foretopsails went up, then the jibs, spanker, and maintopsails. We were out to sea now, where we could feel the long regular heave of the ocean, and so we sailed for a couple of hours longer, till the pilot-sloop Theresa overhauled us. Our foreyards were backed and the ship hove to. The Theresa put up into the wind and lay a little off our starboard quarter. The davit-tackle of the starboard boat creaked. There was a faint splash, and the friends of the crew were hurried away. The picnic aspect was gone; in its place lurked the emotion of a long parting. Soon the boat came for the second and last load. The owners and their friends, the captain's friends, and the pilot went over the side and were rowed out to the Theresa. The crew pulled jerkily and unevenly; it was a far cry to the long whippy stroke of the later season.

And now they rested on their oars, and some one stood up in the stern-sheets, his voice sounding strangely remote from across the water; "A short and greasy voyage!" he called, and the boat and the sloop gave us three rousing cheers. Then we turned to the open sea.

The crew, gathered in a silent group at the forecastle, watched the narrow strip of headland fading slowly away. After a while the breeze died down, and we drifted with the ebb of the tide back  Corralling the Crew |

"A Short and Greasy Voyage!" He Called |

toward Meerschaum buoy. Toward nightfall Cooper screwed up the deadlights; and later, the wind freshening from a new quarter, the last vestige of land soon dropped from our horizon.

As a place in which to sleep the steerage that night apparently was out of the question. On a clutter of chests and dunnage the boat-steerers sprawled, drinking, wrangling, smoking. Some had turned in – turned in mostly as they had come on board, togged out in all their petty shore finery, and now huddled in inert lifeless heaps, or half hanging from their berths, with swollen necks and puffed and livid features.

The floor was littered with rubbish, the walls hung deep with clothing: squalid, congested, filthy; even the glamour of novelty could not disguise the wretchedness of the scene, yet it possessed at the same time a curious insistent fascination. Occasionally there was a trampling of feet overhead, and an order was hoarsely shouted. The ship rolled gently through the oily seas, the wind hummed drearily through the tautened rigging.

When in the morning I awakened I had a very indistinct recollection of my whereabouts. I groped my way to deck, and felt better after a hasty scrub.

All hands were called aft immediately after breakfast, and pacing the deck with hands in his pockets, Captain Gifford gave utterance to various sentiments appropriate to the start of a long sea-voyage:

"Just remember I'm boss on this ship. When you get an order, jump. If I catch any one of you wasting grub, I'll put him on bread and water for a month and dock the rations of the whole watch. You greenies have got just a week to box the compass and learn the ropes; after that no watch below till you do. Let every man work for the ship; I don't mind a little healthy competition between the boats, but if any dirty work goes on, I'll break the rascal who does it. We've got to work together – see? Now go ahead and pick your watches." Straightway the crew was told off into two lots by the first and second mates, and the starboard watch was sent below.

Of our quota of thirty-nine all told, only eight, including myself, were born American; Captain Gifford and the mate, Mr. Hicks, were typical "Cape-Codders," Blacksmith a Pennsylvania Dutchman. Before the mast were two disgruntled farm-hands, one fugitive from justice, and a Fall River striker. Cooper was a Norwegian; Bo's'n, a St. Helena Englishman; Jim, a Nova-Scotian; and August, a "Gue" from Lisbon. All the rest were blacks. Mr. Goomes, the second, and Mr. Freitus, the third officer, both hailed from the island of St. Nicholas. Steward was Bermudian. Smalley (boat-steerer) a full-blooded Gay Head Indian. The South Sea Islands. East Indies. Cape Verdes, Azores, and Canaries, all were liberally represented in our list. Profane, dissolute, and ignorant they were, yet, on the whole, as courageous and willing a lot as one could desire. Being nearly all islanders, brought up from childhood with an oar in their hands, they were eminently suited to the purpose; for boatmen, not seamen, are required in the whale-fishery. |

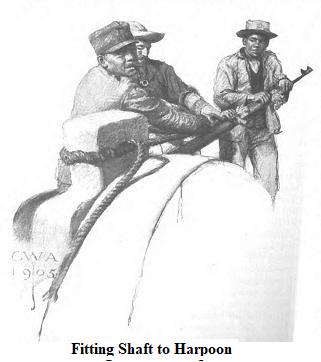

With a Fair WindIn lieu of wages, a whaler's crew, from captain down to cabin-boy, receive each a "lay"; that is to say, a certain proportion of the gross earnings of the voyage. The captain's part may be one-seventh, the cabin-boy's as low as a two-hundred-and-twenty-fifth – called the long lay. Now that we were well out at sea, the work on the boats was pushed ahead vigorously; oars, sails, rigging, and gear of various sorts were assigned to each; harpoons, lances, and boat-spades sharpened and fitted to shafts. The whale-line was stretched and laid in tubs, the kinks being removed by successive left-hand coilings. In some cases the line was even tossed overboard and towed astern; for any hitch when it is racing out the chocks, fast to a gallied whale, may mean loss of both lives and boat; and both are equally precious. There were two of these tubs to each boat, containing between them over half a mile of manila rope two and one-half inches round. Each boat-steerer conducted the arrangement of his own boat, under the immediate surveillance of his boat-header. In less than a week's time we were ready for whales, and once more the foremast hands were ranged up along the lee-rail midships. This time the boat's crews were to be chosen – a far more serious affair than the mere selecting of watches. The experienced boatmen formed one end of a long line, the green hands the other. Like judges before a dog-bench the mates strolled up and down the row, now feeling this man's ribs, now making that one bare his arm; occasionally pausing to jerk out a question: "Ever pull in a boat? No? What in – are you good for? Where are you from? Talk English? Oh! you pulled in Mr. Diaz's boat last voyage; eh? Well, I wouldn't give a for any man he broke in!" The boat-steerers lounged interestedly in the background, now and then proffering suggestions to their heads. When the inspection had been finished, the drawing began. It was evident that the material had been studied critically, for there was but little hesitation and but few words were spoken. Now and then there was a grunt when a likely man was lost, or occasionally a mate in a low tone referred a decision to his boat-steerer. When the ceremonial was over, much to their chagrin not one of the whites before |

the mast had been assigned to a boat. All were left for ship-keepers. Six men make up a boat's crew. The mate "heads " – that is, commands – the boat, and so is called the boat-header. The harpooner or boat-steerer pulls the forward oar in approaching a whale. After "getting fast" to it he goes aft and steers the boat, giving place to the mate, who goes forward to wield the lance in the killing. The whale-boat is a clinker-built "double-ender," some thirty feet long, six feet in beam, with a very pronounced sheer to enable her to ride in the roughest weather. She is sloop-rigged and fitted with a centreboard and a collapsible mast. From the decked-over stern juts a round post, called a loggerhead, around which to snub the whale-line. The stem is deeply grooved and set with a roller. Through the "chocks" thus formed the whale-line runs out, being kept from jumping by a slender wooden pin. The boat is provided with both rudder and steering-oar, the latter twenty-three feet in length. Every man before the mast, the boatsteerers and the mates, must do masthead duty. In the arctic fishery a "crow's-nest" is erected to shield the lookout from the severity of the weather, but until of comparatively recent date not even the hoops were used in sperm fishery, the "masthead" steadying himself by hanging over the royal-yard, the supposition being that the insecurity of his position would tend to keep him wakeful. But the means failed of its purpose not so infrequently as might be supposed, the result usually being fatal. To-day the use of the hoops is universal.

We had arranged our boats' crews one evening after supper, and the next morning for the first time we posted our masthead lookout. Standing on the upper crosstrees with arms dangling over the hoops, great spectacle-like rings bridging the royalmasts breast-high, the green hands tasted their cup of misery to its dregs. For each graceful dip and gentle roll, which on deck was scarce perceptible, augmented by the hundred feet of sheer mast was exaggerated a hundredfold, till the vessel seemed to plunge and rock like a maddened cow-pony, and the reeling masts starting on their dizzy downward course appeared about to plunge the very trucks into the yawning depths. Captain Gifford had offered a bonus of five pounds of tobacco to whoever raised the first whale taken, and with this added incentive four men scrambled up the weather-shrouds, and finding their places in the hoops, with glasses and naked eye scoured the seas eagerly for |

the least sign of whales. On deck quiet reigned, and with all sail set the ship held southward. After a second night in the steerage, I concluded it was full time to move to the cabin, particularly as I had noticed that Cooper, now his supply of liquid friendship had diffused itself, was pondering somewhat on the inconvenience to which he would be put in welcoming another to his already crowded quarters. Our stateroom had originally been a part of the sail-pen, but when the previous accommodations had proved inadequate it had been annexed to the cabin. It was scarcely larger than a good-sized dry-goods box, and an average man could not stand erect in it. Here I had a fore-and-aft berth, the upper one. Our only port opened directly into it, and, worse than the leak, the stench from the bilge reeked up through the trap. It was a simple matter after I had turned in of a night to span with one hand the distance from nay nose to the deck planking. Hard by my head slept Cooper; beneath me slumbered Steward. In the slight floor-space remaining after the bunks had been set up reposed our several sea-chests. But two men there were on shipboard who did not retire for the night in the same garments they had toiled in during the day. In the morning we all lined up to the water-butt, lashed amidships for the purpose, each with towel thrown over his shoulder and tin basin and soap in hand. After bailing the requisite amount of water through the hung-hole by means of a "thief" – a method sufficiently tedious to insure no waste of the precious fluid–we would place our basins on the edge of the hatch-cover and pursue our ablutions; then take the basin back to its little rack in the ceiling of the roundhouse. At the forecastle salt water had to suffice.

There are three messes aboard a whale-ship – cabin, steerage, and forecastle. Mr. Hicks, Mr, Gnomes, and myself sat at the captain's table. At the second table Cook, Steward, "Boy," Cooper, and Mr. Freitus pitched in indiscriminately with no attempt at ceremony. The steerage had a table of their own and a boy to attend to their wants. But in the forecastle each black, when his watch was called, reached for his pot and pan, glided aft to the galley down the leeward side, received from the Doctor his chunk of meat or daub of hash, two hot potatoes, and a "tub of slop," and wiping his sheath-knife on his jeans, sat down on his chest, with the pot of coffee safely propped between his hare feet, and lived purely for the enjoyment of eating in the good old-fashioned way. Our food was, of good quality; rather coarse perhaps, but wholesome. In common with most people, I once had an impression that whaling was a lazy, aimless sort of existence, with of |

course occasional periods of activity, but in the main void of exertion, listless, and enervating. I soon had this idea shaken out of me. I have never seen men toil more unremittingly; here at least the hours in which a man might labor were not limited. Often the work of the day was carried on throughout the night-watches, and Sunday meant nothing when whales were alongside or sighted. A storm served merely as pretext for repairing sails not set, and the top-hamper was gone over in the nastiest of weather. New sails were made, spars scraped and slushed. rigging served and tarred, repent and stiffened. Chafing-gear was braided, the gallows over the try-pots remodelled. Day after day of glorious weather now succeeded, and under a full spread of canvas we bore south and by Bermudas, veered east, and on one long leg made the Western Grounds; passed Azores, passed Canaries, and cruised back again over a part of our course before making southing. Then we struck the southwest trades and bowled merrily along with a following wind, the sun always shining and great banks of fleecy biscuit-shaped clouds hovering constantly over the horizon. Countless schools of flying-fish rose continually at our bows and scattered like autumn leaves to leeward. Dolphins darted in opalescent gleams in our wake; and Cook and Steward and I angled for them. On some mornings the sport was quite exciting. It was "Cook," I believe, who flirted a fish completely over the poop, smashing in the companion, the occasion but serving as opportunity for the still further enhancement of my appreciation of the mates' astounding vocabulary. Every morning before sunrise coffee was served to all hands and the lookout posted. An hour after breakfast Captain took his sights and went below and worked up his departure. Before dinner he again took the sun to fix the longitude. The watches changed at four, eight, and twelve, and at six in the evening. Every two hours a fresh gang relieved the man at the wheel and the masthead lookout. At four, decks were scrubbed down and the pumps tried. From the time the lookout took their places in the hoops at daybreak till the cry – " Alow from aloft " – brought them tumbling to deck at nightfall, no noise of any sort was permitted. But then in the second dog-watch the hands gathered about the windlass or stretched at full length on the forehatch; smoked, yarned, and indulged in horseplay as they desired. The green hands perhaps studied the points of a dummy compass, or under competent teachers fingered the ropes, committing them to memory. Two misfit concertinas every night sent up their dismal wail to a tune which never varied, often keeping time with the strokes of a couple who pounded up hard bread to be mixed into a molasses mush for the watch they belonged to. The boa t-steerers lounged on the work-bench aft the try-pots, whetting harpoons and swapping stories. Mr. Hicks and I often would sit on Cooper's chest, before the roundhouse. tying knots, talking of home and of past gastronomic achievements. We had drifted into the habit of meeting two or three times a day whenever there was opportunity. Early in the cruise, when he was still convalescing from an illness of the previous voyage, we would sit together out on the main upper topsail through the quiet hours of the afternoon. Swaying gently to and fro on our mammoth pneumatic cushion, surrounded by great banks of billowing canvas and shut completely off from all view of the deck, Mr. Hicks would expatiate at length upon the habits of whales and his own observations of them. "There are only two kinds of whale," said Mr. Hicks. "One of 'em is the sperm-whale; the rest of 'em is the other. The sperm-whale is mainly valuable for his oil (sperm-oil, you understand); has teeth only on his under jaw like a cow, fights at both ends, has one forward spout, and lives only in warm country. Now right-whale oil ain't worth beans; you hunt him for bone; 's got a whole sieve made out of slabs of bone in his mouth instead of teeth. Then he only fights with his flukes; but you bet he can use them pretty lively. Never known of a right whale's crossing the Line. Swallow Jonah? Humph! Well, a sperm-whale could a-done it, but how'd you like to swallow a woolly worm? No wonder it went agin' his stomach." |

The Boats Were Launched |

Again we frequently met in the larboard-quarter boat when decks were flushed at night. Usually he would be chewing a piece of raw salt codfish gleaned from a box Steward had stowed under one of the spare boats. It was from this point of vantage I was startled one day by an unusual commotion forward. We had driven into a school of porpoises, all breaching and gambolling about us. There was a scramble for harpoons, and in a moment the boat-steerers were out in the bowsprit-shrouds in a race to get fast. There were two misses before Smalley drove his iron into one, for a porpoise's movements are as erratic as a rabbit's. Flopping and bleeding like a stuck pig, the animal was hauled to deck. That night we had the first fresh meat in weeks, and for two clays we feasted on porpoise steaks and liver. The steaks are a trifle oily perhaps, but the liver is as good as any. Sea-pig he is called by the sailors. The cook tried out the head oil, the cabin-boy saved the teeth, and Mr. Goomes cut the crotch from the flukes for a talisman and nailed it to the cutting-stage – the first catch of the season.

No work beyond the sailing of ship and keeping the lookout is required on Sunday unless a whale he sighted or there is oil to Bare for. The ship presents on that day long lines of fluttering garments strung from davit to davit; patched, quilted, abbreviated, till all semblance to the original scheme is lost. Laundry-work attended to, the next thing in order seems to be the cutting of hair. The less energetic sleep; others read the magazines furnished by the several charitable societies ashore. Some write letters, some patch and mend, but always aloft four pairs of eyes scour the sea for whales, and the ship holds her course. One Sunday morning a tremulous "Bl-o-o-w!" from aloft brought me to my feet, trembling with excitement. "There she blo-o-ows!" thundered from all four hoops. "Ah blo-o-ow!" Captain shot from the companionway and bolted up the main shrouds. "Where away?" shouted Mr. Hicks, dropping his piece of salt codfish. "Two points off the lee bow, sir; school sperm-whale," answered Bo's'n. "Keep her steady, Mr. Ilicks," called Captain, squirming by the maintop. "Ah bl-o-ows!" chorussed the mastheads. "There! she white-wa- ters!" "What time is it?" shouted Skipper from the topmast shrouds. "Quarter past nine!" yelled Cook, craning by the shoulder of the helmsman. Feverishly the decks were cleared, the men gathered in their lines of washing, the boat-steerers gave the last few touches to their boats and cleared the line-tubs. The whales now had sounded. In suspense we on deck leaned over the bulwarks and gazed to windward in the direction they had gone. At last, after what seemed an interminable wait, an instantly stifled "B-l-ows!" sounded from aloft. "Lower away!" came the order. In the midst of a breathless excitement the three boats were launched, the sails hoisted, and a long beat to windward began. The whales spouted but a few times and then went down again. When they again broke water, for a second time, it was at least eight miles from the ship, and a signal was set to recall the boats. In the Sunbeam's log-book is the brief but significant entry. "Raised whales this A.M. going quick, lowered, no success, come on board." We shortened sail at sunset for the first time, and afterwards we cruised through the day, and at night carried barely enough canvas to keep our steerageway. [TO BE CONCLUDED.] |

HARPER'S

|

| Vol.CXII | MAY, 1906 | No. DCLXXII |

The Blubber HuntersBY CLIFFORD WARREN ASHLEYPICTURES BY THE AUTHORII — TAKING WHALESWe raised our next whale at sunup on another Sunday some weeks later, and almost before the first long-drawn "Bl-o-o-w" from aloft had ceased its echo our boats had dropped like shadows on the surface of the desert ocean. One moment the decks had been hushed and quiet. The next it was as if a squall had struck us – a hurricane of orders preceded a wild stampede, and underfoot was instantly strewn with a tangle of braces, sheets, and halyards thrown by the mates from the pins. The men reached and hauled, the mates slacked away, the great yards swung, and the old bark slowly came about. Shoes were kicked from feet, and while we still luffed, the bow boat took to the water with scarcely a ripple, and the boat's crew swarmed down the falls and dropped catlike into their places. With a whir of tackle the waist and starboard boats followed; so closely, they seemed almost to strike the water in unison. Carried away in the excitement of the moment, I forgot a pair of burned hands I then was nursing, and brushing aside one of the regular boatmen, I slid down the davit tackle, and found myself in the mate's boat, struggling with the rest of the crew in the maze of gear. Wallowing precariously in the heavy wash, we balanced on gunwale and thwart and swayed and stepped the awkward swinging mast, then made fast the stays. The sail was hoisted and peaked. the sheet paid out, and with the boom sousing through the water we started clown the wind full thirty yards ahead of Mr. Freitus. The boats were soon widely scattered. Occasionally another could be seen when the seas at the same instant tossed both of us high. The Sunbeam in the distance showed only her top-hamper. Of the whereabouts of the whale we were advised from time to |

time by her signals aloft. The colors soon had disappeared from the main-truck, indicating that the creature had sounded. So we held our course unaltered till the weather-clew of the fore-t'-gallants'l told us he had broken water far off to our windward, and there was nothing left but to in sail and pull for it. For four hours or more we tugged at the oars, changing our course from time to time to suit the varying whim of the whale; several times we were almost within "darting distance," when he turned flukes and sounded. So we pulled down, perceptibly gaining nearer, and the chase every moment becoming more and more intense. We strained at the oars till the mate, crouching by the stern-sheets, was blurred to our sight, and brilliant specks of light danced before us; our throats were parched, our hands were bleeding. Suddenly, "Stand by your iron, Tony!" and from somewhere back of us came a faint, sonorous whistle. I twisted my neck, and caught a glimpse of a dark mass cleaving the water a hundred fathoms ahead. Our oars bent like reeds, the boat leaped ahead like an animal under the lash. Stooping low over the steering-oar, Mr. Hicks jerked out crisp words of encouragement to us. Again the whale spouted nearer, and then, for a third time, that long-drawn whistling exhaust; and the humid vapor escaping from the pent-up lungs drifted like a mist over the boat, and we felt on our necks its dampness. The rankness of it was still in our nostrils, when there were a swirl and a rush, and the huge monster breached clear of the sea, and with mighty flukes tossed high, for an instant was silhouetted against the yellow of the afternoon sky; then, with a deafening roar of displaced waters, disappeared beneath the surface, just as another whale, coming from we knew not where, broke water under our very bows. "Give it to him!" yelled the mate. Tony gave a frantic lunge, and the harpoon was buried to its bitches; overboard went the second iron. "Fast, by – ! Peak your oars! Get out of the way of that line! Empty some water on that loggerhead, you – lubbers!" and with a dash over the tottering thwarts, Tony and Mr. Hicks shifted places. A jerk pitched those unprepared in a heap to the bottom. For an instant our stem was sucked  Overboard went the Second Iron |

under and we shipped a barrel of water. Then we were off with the speed of an express, with the water pouring in a sheet over our bows and sifting the full length of the boat, till the last of us was drenched to the skin. Writhing and squirming from tub to loggerhead, from loggerhead to chock, under the kicking-strap and along the channel formed by our peaked oars, the line whistled and tore, sometimes with a rumble like the roll of drums, sometimes with the wailing shriek of a siren – whistled till it smoked, yet still the boat was being lashed through the water like a fly on a trout-line and behind us rolled up a wash like that of a steamboat. The water boiled at our bows and eddied by our quarter, leaving a line of suds behind us far back to the horizon. Buffeted from side to side by the oncoming waves, the boat creaking and quivering under the impacts, we tore in an arrowlike flight due westward, till the ship was but a speck in the distance. Tony stood by the stern-sheets, a canvas patch in hand; from time to time he threw a turn of the line over the loggerhead, sometimes cast one off, but only to go on again the instant after. And so we held our pace without letup; for though, after a while, the whale slackened his first mad pace, the line also went out slower, and ever the bow of the boat was kept just above the level of the water. And we, crouching in the bottom to steady her, bailed constantly to keep from filling with the influx over the bows. Slower and slower the line surged, but the stern tub was emptied and the waist tub was being drawn on heavily. Then carne a moment when it ceased running through the chocks and the boat began to lag. "Stand by to haul in line!" came the order, and getting out of our cramped positions, we grasped the now inanimate rope and hauled and strained with feet braced on the thwarts, winning it back inch by inch, painfully and slowly, Tony holding what we made with his turn on the loggerhead. Span by span, fathom by fathom, the line crawled in, and we coiled it aft in the bottom.

Gradually we hauled up to the whale, and our nerves tingled again in breathless suspense. With knee braced in the clumsy cleat, Mr. Hicks stood ready, his lance poised high. We dragged np abaft the churning fluke, then got out our oars and pulled till we scraped the barnacled flanks, "wood to black-skin." Almost bending double, Mr. Hicks ground in the lance till it brought up at the socket, a full six feet of cold steel: then for an instant the whale "churned." The great fanlike flukes lifted from the water; gently they seemed to tap the surface, but |

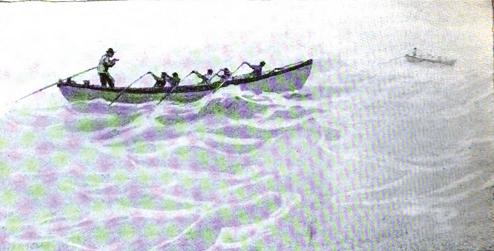

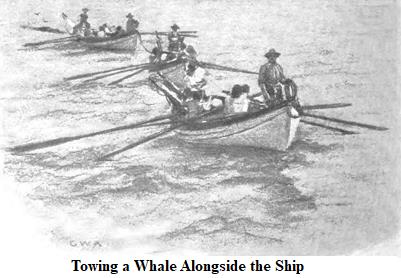

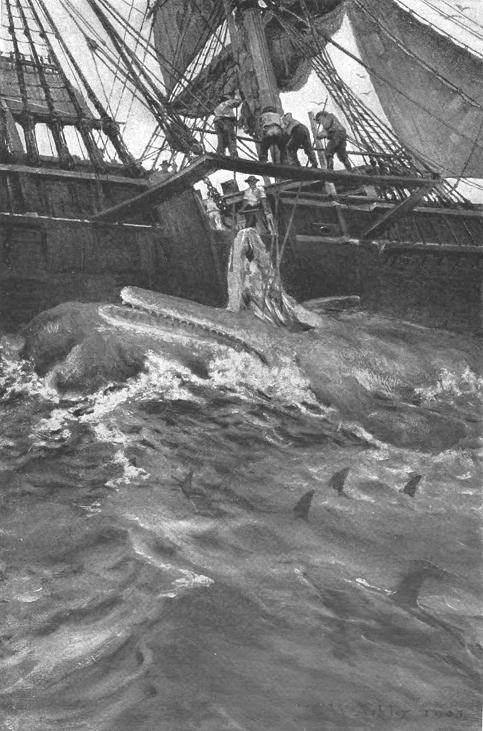

the report was like that of a cannon, and the other boats, two miles away, caught its reverberations. "Vast pulling! Stern all! Peak your oars!" and we watched all that coil of line, fruit of an hour's toil, roll over the bow again, to be hauled in anew. But our quarry was now spouting thin blood and visibly growing weaker. Four wearisome times, hand over hand, we hauled up to and lanced him. Each time he carried out less of our line. He no longer swam with the decision of his first frenzied flight, but frequently altered his course, spouting oftener and thicker and with visible effort, and behind him he left an ever-darkening trail of crimson. Then, when we were still at some distance, as though goaded afresh, he churned his flukes, and with vast form listing to one side, tore with some suggestion of his original pace in a large arc around us. Suddenly he veered sharply; then, with a horrid inward convulsion, a stream of clotted crimson gushed from his spiracle, and the great carcass turned belly up, with the seas lapping over it – lay just awash, a huge, shadowy, undulating mass, with no more semblance to a living creature than had the seaweed drifting by it. Already the scavengers of the deep were gathering, their sharp fins cutting the water knifelike all about us. Not a moment could we halt; the day was all too short for the task before us. Reeving a short warp through the spout-hole, we passed a line from one boat to another, and, all tandem, began the long dead tow to ship.

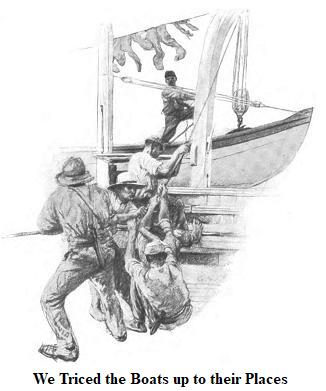

Luckily the Sunbeam crowded sail, and with a favorable wind bore down to us. After what seemed an interminable pull we dragged the carcass alongside and passed up the tow-rope. With a rattle and jangle the fluke-chain was belted, and heaving away at the windlass, the whale was soon fast alongside. As we rounded the Sunbeam's stern to get under our davits, the grateful aroma of coffee greeted our nostrils, and with renewed energy we clambered to (leek and triced the boats up to their places, swung the cranes, and fastened the gripes. "Dinner, all hands! Dinner, Cook, dinner!" There was a stampede aft, and with a clattering of pots and pans the half-starved crew mobbed the galley in a fight for double rations. A whale-ship "cuts in" a whale always over the starboard side. To admit of this, three of the four whale-boats are suspended from the port side, while to |

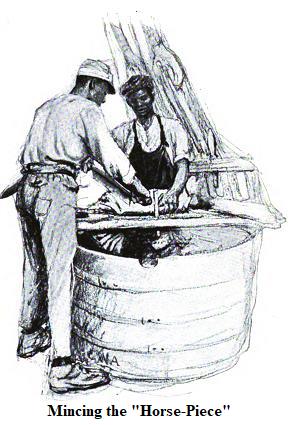

starboard, over the gangway, is lashed a long platform, or cutting-stage. This is lowered from the ship's side and boomed out some fifteen feet over the dead whale. From this platform, which has a hand-rail, the mates work, cutting at the blubber with long-handled, keen-edged spades, similar in shape to those used to clear ice from sidewalks. If the weather is not too rough, a ship will "cut to windward" (with the whale on the starboard side toward the wind). By so doing the wind pressure on the sails will counterbalance to a greater or lesser degree the weight of the cutting-falls, and so tend to keep the ship on an even keel. The strain at the mainmast is terrific. Several instances are on record where the weight of a whale's head has caused the foot of the mast to crush through a vessel's back-bone, so scuttling her. The cutting-tackle consists of a duster of gigantic blocks made fast to the maintop, through which are rove the two falls, each suspending a heavy block and blubber-hook. This cluster of blocks is braced well forward with a jigger, in order that the two hooks may swing directly over the blubber-room at the main-hatch. The blubber, except for a filmlike coating called blackskin, easily scraped off with the thumb nail, is the only outer covering of the whale. It is of a fatty nature, but is of very close texture and exceedingly tough. This separates readily from the flesh beneath, so that in cutting, only vertical incisions are made with the spades, along a general line termed the scarf, and the lift of the windlass rips the blubber from the carcass as the peel is skinned from an orange, requiring only an occasional jab from the spade to keep it free, the whale rolling over and over in the water as it is unwound, the mates on the stage hacking with their spades a corkscrew line about the rolling body, the windlass tearing away the blubber. When the end of the strip has been hauled to the lower masthead, the third mate at his station in the waist, with a long boarding-knife punctures two holes through it close to the deck and at some distance apart. Through these a chain strap is rove and the second fall attached to it. Then, all hands standing back from the gangway, with a few well-directed lunges the mate severs the mass above the newly fastened tackle, and to the lusty shout of "Board ho!" the great weight of the first "blanket piece" swings inboard, sweeping any luckless obstacle from its path, and dragging about with it those who are attempting to steady it down the hatchway. The day was too far advanced when we got our first whale alongside to do more than get the fluke-chain in place and prepare for an early start in the morning. During the night the wind freshened, and by morning was blowing half a gale. The ship labored badly, with the whale's enormous bulk jerking and bumping alongside. After the expenditure of an infinite amount of patience and labor, the first, blubber-hook was embedded at the base of the left fin and a semicircular cut made below it. With the carcass yawing and twisting, the seas continually breaking over it till it was often submerged completely, not one thrust in six of the cutting-spades was effective. To get the hook in place it was necessary to send down a man. "Who's overboard?" Mr. Goomes asked. From a dozen volunteers one was selected – a big, hulking negro, distinguished from the rest by a wide cotton rag he wore under his jaws to keep his hat in place. Giving the mr,n chance to remove only his coat, a "monkey-rope" was fastened about his waist, anc he was dropped sprawling on the slippery, heaving flank of the whale. About him hovered innumerable sharks, gliding like shadows alongside, now and then tearing away a hunk of flesh and flopping silently off, pursued by others equally ravenous. With lines a couple of us eased the weight of the enormous blubber-book while the negro groped for the hole made near the flipper. The mates, with backs to the hand-rail, fought off the sharks from too close a proximity. The seas constantly broke over him, and twice the man was washed from his task, and was only preserved by the rope about his waist from being ground between the whale and the ship's side. Then, with the hook in position, the windlass crawled up on |

Cutting-in the Whale |

the slackened fall so slowly that the poor fellow seemed to be under water for nearly a minute hugging the hook to its place. Suddenly the ship yawed, and then with a slap and a jerk the fall tightened. There was a hollow rending sound, and the blood-dripping semicircle of blubber lifted from the carcass, with the disjointed fin flopping at its end. As the ship rolled far over, the carcass raised a third of its bulk from the water, then settled suddenly back with a sullen splash, and a straightened blubber-hook jerked high in the air and fell with a crash on deck. The whole wearisome process was to be gone through with again. A second hook having been fetched, it seemed about to hold, when a sea a little larger than common broke completely over the stage, and lifting the whale bodily, crashed it up under the stage planks, and would have carried away the mates but for their lashings; as it subsided, the whole weight of the whale was thrown suddenly on the tackle, and the second blubber-hook was left dangling in mid-air, so much junk.

The officers by this time were all well out of patience, and the crew naturally had to bear the brunt. Orders followed each other in a torrent, and were no sooner given than countermanded, the whole interspersed plentifully with curses for the fancied stupidity of the crew. A little late in the day, perhaps, it was decided to tack ship and cut to leeward. Our unwieldy burden, acting as a "drug," made it impossible to get up headway sufficient to put over directly. So over two hours were spent wearing ship. For a long while it looked as though even this was not. feasible, but at last we got about, and were well rewarded by the comparative quiet in which our cut lay. We swayed the stage a trifle higher to allow for the starboard list of the ship, and the wind having abated considerably since early morning, but for the heavy ground-swell no easier cutting could have been desired. The only remaining blubber-hook – a new one and much larger than the others – was broken out, and for the third time a man went overboard to secure the hook in place. It would seem that we had received our due of accidents. Yet no sooner had the blanket been well started toward the maintop than a sudden lurch gave an extra strain to the fall, which was an old one. It parted and the block, tackle, and our third and last blubber-hook went clanking overboard. While Cooper hewed an old-fashioned toggle from an oaken plank, the rest of us sat down to.a glum meal in the cabin. Skipper even omitted his customary joke – a threat to tie his napkin about the cabin-boy's neck, when that individual had forgotten to fetch it. We faced at this juncture the dismaying prospect of cutting-in a whole voyage without a hook, and the outlook was anything but cheerful. So dinner was bolted in a |

gravelike gloom and the work on deck resumed directly. A chain strap having been with considerable difficulty shackled about the lower jaw, the body was rolled over, and there, pinned by the strap in the angle of the jaws, were the missing block and hook. How they had remained in such an insecure position is a mystery. But no time was given to speculation. A fourth man plunged recklessly overboard without pausing to make fast the monkey-rope, and three more sharks gave up the ghost. Seven hours' arduous labor performed and our job as yet unstarted! But if all things before had seemed to hinder, all now seemed to facilitate matters. A new fall was rove through the blocks, the hook was lowered from the cutting-stage and dropped directly into the hole without necessitating a man's going overboard. The blubber lifted easily; the ship rode quietly; the work progressed without a hitch. The carcass was decapitated; the head secured astern. The body rolled over and over, weltering in gore, the great dripping blankets followed each other up the alternating falls. Mr. Freitus by the gangway sliced with his boarding-knife and swung the pieces inboard. Cooper perspired over the squeaking grindstone, muttering curses on those whose continual call, "Sharp spade! Sharp spade!" kept him "bumping." Between decks, in the blubber-room, one watch stowed back the "blankets" and cut them into smaller "horse-pieces." Above, the other watch steadied the huge chunks by the hatchcoamings and lugged the heavy block and chain back to the gangway, slopping and sliding in the slush and gurry. Moving too deliberately from the path of one of the inswinging blankets, one of the green bands was swept from his feet like a tenpin, carried across the deck and slapped down the hatchway. He managed to work out the remainder of the day, but for the rest of the season was on the sick-list. About us in a great circle the waters were quite crimson with the outpour of blood from the carcass. The sea fairly boiled with monstrous sharks battling among themselves for the detached fragments. The work was progressing smoothly, when suddenly the ship lost her headway, and a faint, all but imperceptible tremor was felt in the deck. We were already hove to; now we made sternway. It seemed almost as though some curious unknown current had seized us. The whale swung from under the stage, making further work impossible. The men exchanged superstitious glances; the mates stared aloft, but everything seemed drawing properly. Suddenly a shriek from somewhere aft broke the strained silence, and Steward struggled from the rear of the galley, dragging hapless Cook by the ear. "This – nigger been an' harpooned a shark!" Sure-enough, furiously lashing the water into a foam astern, a thirty-foot shark was just succeeding in freeing himself from the cook's investigating iron, made fast to a cleat at the taffrail. The ship, freed once more, serenely gathered headway, the whale swung in, and all hands resumed their labors. The spiral cutting progressed to a point midway between the hump and flukes; then, after the body had been disembowelled and searched for possible ambergris, two vertebra: were disjointed and the carcass cast adrift. Hauling the remnant partially from the water, the flukes were severed at the small, and, freed of the chain, followed the denuded carcass down to the sharks. To the exultant cry of all hands, ",Five-and-forty mo-o-ah!" the shank of the tail smashed over the sheer-plank and spun across the deck. We hoisted the junk and made it fast to the lash-rail, aft the gangway. Then came the case, the real lift of the day. Its thirty tons or more brought the starboard scuppers down to the water-level; the ship's hull cracked and groaned under the strain. Half on deck, half by the board, it was secured fast and the stage hoisted out of the way. "All hands aft and splice the main-brace!" came the welcome call. And further work on the whale was stayed till observance was paid to this time-honored custom. It may be that the hearty bawl when the last of the cut swings inboard is as much due to the anticipated grog as to the five-and-forty barrels nearer "full ship." Standing by the quarter-deck, our skipper dealt out the stimulant from a cracked and brim- |

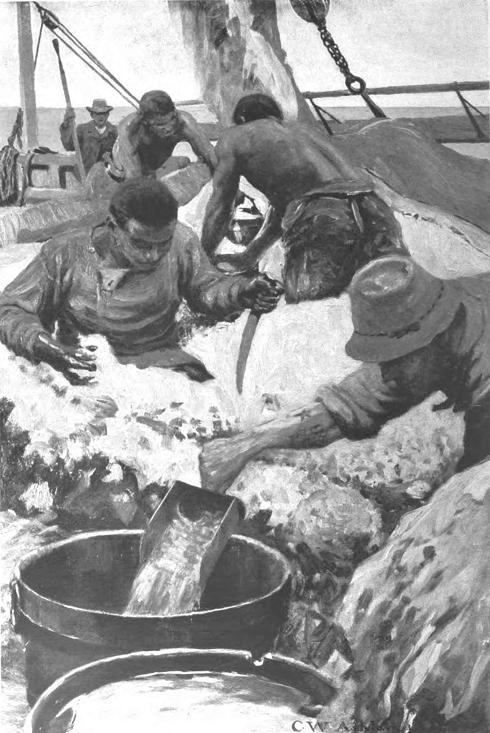

They Half Cut, Half Ladled the Barrels of Pulpy Substance from its Cells |

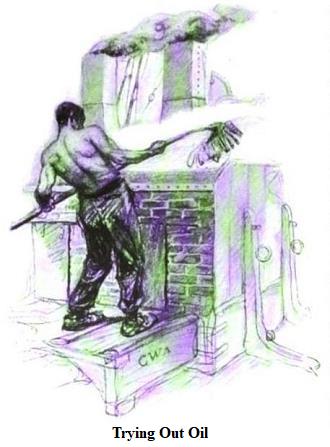

ming pitcher. Filing past, each man in turn received the tumblerful, and tossing the raw stuff at a single gulp, passed forward with watery eyes. "Bailing the case" is perhaps the most interesting of the several processes peculiar to whaling. After the "splicing of the main-brace" some portion of the litter had been cleared away from deck and the cutting-tackle sent down. A hurried supper was partaken of after which one watch was sent below and the other turned to preparing the try-works, cutting horse-pieces, and lastly bailing the case. The decks were lighted with a few thick-globed lanterns, which diffused a feeble radiance over the scene. The tail of a beaver, the hump of a camel, and the case of a sperm-whale have each the same function – the hoarding up of reserve nourishment against a time of fast. Fatty and unctuous, glistening and pearly white, the cavernous reservoir lay opened before us like some vast comb of honey, trickling its stored-up treasure over the sullied planking, turning it to purest snow. Stark naked, three negroes climbed into its tanklike interior, and wallowing up to their waists, with knives and scoops, half cut, half ladled the barrels of pulpy, dripping substance from its cells. With coal-hods, tubs, and pails, an improvised bucket brigade passed the prized contents forward to the try-pots, where two bronzelike figures, standing in the capacious kettles, with groping fingers tore the oozing pulp to shreds. Delving deeper and deeper with an eagerness requiring no encouragement, the bailers labored without cessation. The try-pots were filled, but still the supply held, till thirty barrels and more of pure spermaceti stood in brimming tubs along the bulwarks. The scuppers had been stoppered, and the deck washed inches deep in gurry and congealing case-matter. Through this the men splashed and slipped, and with scoop and shovel reclaimed the precious leakage and poured it into tubs. Under the try-pots fires were started, and the flames leaped hungrily high above the funnels, throwing a lurid glare over the shifting scene. Above, the wan ghostly sails flapped and glowed, the flames contorting wildly in the back-draught caused by the flapping. Black toiling figures teemed like ants about the decks; and all made a picture the weirdness of which suggested a transcript from the nether world. Like a presiding evil spirit, Smalley's dark face shone in the intense heat before the works as he forked the minced strips of blubber and soused them in the seething caldrons. Watch relieved watch, but all through the night the work went on. The horse-pieces were minced, the tried-out "scrap" was fed to the fire. Black smoke belched from the chimneys, darkening with a cobwebby soot the rigging aloft and the near-by bow boat. The tried-out oil was bailed to a temporary cooler. More blubber was fed. The men, passing by, helped themselves to choice bits of well-fried scrap. A pungent, sickening odor of burning fat burdened the air. In the morning we sighted another New Bedford whaler, also boiling, the schooner Eleanor B. Conwell. But before there was opportunity to speak her we again raised whales, and by noon had another alongside. In a drizzling rain we finished cutting-in and stowed the damp blubber between decks. The second morning the Portuguese skipper of the Conwell came over with a boat's crew and gemmed with us; during his stay on board his crew joined in the labors with ours, and as they worked they discussed the comparative merits of the two ships, their captains, and the fare. Mr. Goomes, myself, Tony, and a boat's crew lowered in the starboard boat and cruised till nightfall with the schooner. In the heavy ground-swell running she made bad weather of it, the big boom thrashing from side to side, jarring and racking the whole craft. The steward was the only white man aboard, and he made a melancholy tale of his trials with the captain, who, he said, permitted him no molasses to cook with, no yeast for his bread, and as for butter, "why, the blamed Gue eats lard on his bread, and thinks a white man oughter." The crew were a wild lot, and already underfed; their mutiny a few months later might then have been predicted. I came back to the Sunbeam minus a jack-knife but with my pockets full of gingerbread. Our pots could try out about two barrels |

of oil an hour, and at this rate we now had perhaps fifty barrels of all but boiling oil in the large metal coolers between decks. Driven aft by the heat, the cockroaches that night literally swarmed the cabin. Time and again we were awakened by their running across our faces. Pulling on my boot hurriedly in the morning, I encountered no less than six of them. Almost under the try-pots, and with the floor buried in a heap of musty and mildewed garments, wet and oily from constant duty overboard and contact with the dripping blubber, the rat-hole of a forecastle, with its twenty occupants, must have been a veritable hell. The wet blubber between decks began to rot within twenty-four hours after being stowed down. Which was the more obnoxious, the burning scrap on deck or the decaying blubber below, is difficult to determine. That night I attempted to sleep on the galley roof, propped against a line-tub. At 2 A.N. there was a miniature cloudburst, and I went below and spent the remainder of the night in a temperature of 162°. If anything, it was hotter below the second night. I had planned to sleep under one of the spare boats, but found Steward and Cook occupying the only suitable place. I determined to risk another night on the galley. There was scarcely any breeze blowing, but the flapping of the spanker to the ship's pronounced roll made a considerable draught, which fanned my face unpleasantly. Half a mile off our beam the Conwell pitched and rolled, boiling her oil. Her sails were ruddy in the light from the try-works, which cast a dulled reflection over the water. I went to sleep with its baleful glow dancing confusedly before my eyes, and, perhaps as a consequence, was tortured by the most blood-curdling dreams. In the end a realistic whack brought me to my senses, and I wildly grabbed the davit I had struck against, barely in time to save myself from going overboard. Rolling up my blanket, I started below, noticing with a shudder as I passed the binnacle that the man at the wheel was sound asleep. There was not another person to be seen about deck.

We raised whales again within the week, and for a second time the five pounds tobacco reward fell to Bo's'n. The commotion of the other occasions was repeated. Amid creaking of blocks, flapping of sails, shuffling of feet, the babel of orders and curses, and the crew's hearty "aye, aye, sir!" covers were removed from line-tubs, casks and stores hurriedly lowered to the hold, breakfast swallowed, and in fifteen minutes the boats were sent down and a long pull to windward ensued. On account of my hands, now in bad shape, I this time remained aboard ship. After the boats had lowered I slung a pair of field-glasses |

about my neck and joined Captain in the hoops. The day was hot and sultry, and the water reflected the sun's blinding glare into our eyes. 'Way below us the pygmy seamen scurried about deck, handling ship, and setting the various signals to keep the boats advised of the whales' whereabouts. Evidently we were pursuing a large school this time, for the spouting was continuous. So the colors stayed hauled to the main-truck. After a long chase one of the boats got fast, and the panicky flight of the whale soon carried them all but beyond our vision. I went to deck and stretched my legs and again took my post at the lookout in time to witness the flurry. While we were absorbed in the culmination of the distant tragedy, Cooper announced from deck the sighting of another whale. Sure-enough, not two hundred fathoms off our quarter, another leviathan was steaming up, logging about two feet to our one and heading directly across our bows. He swam so near, not varying his course, that a collision seemed imminent, and recalling the fate of other vessels that had permitted a whale to ram them, Captain Gifford became alarmed and ordered those below to make all noise possible. So they pounded the deck and the water-butts with cord-wood sticks, pumped the squeaking windlass, clanged the ship's bells, and banged tin pans. Amid the clatter, but with a dignity consistent with his proportions, the whale settled from sight and passed under our bilge and away. Under a fair wind we now ran down and picked up the waiting boats, and so got the second "cut" alongside.

From then on we captured whales in rapid succession, till one day we raised another solitary bull, and took to the boats on sighting him. Ours had lowered first, and we were full and going free before the next boat, Mr. Goomes's, swung from the cranes. Just before she took the water the forward tackle fouled, and the boat's stern swinging under the Sunbeam's counter, just settling in a swell, the stern-post and steering-oar brace were smashed to splinters and the rudder put out of commission. We left Mr. Goomes stretched at full length over the cuddy-board, furiously rigging a jury steering-gear, and jabbering, while he worked, a stream of Portuguese oaths, impartially directed at both his crew and the job. But the chase was a long one, and when we finally got an iron to the whale it was from Mr. Goomes's boat, and later Mr. Freitus closed in and got fast also. It was toward the end of the afternoon that we found ourselves racing abeam of Mr. Goomes and within ear-shot of the labored spouting of the whale. Mr. Hicks and Tony quickly shifted places and we pulled up beside the fugi- |

tive. Quickly the varying orders came: "Give way all! – Vast pulling Three! Pull Three! – Stern Two! – Vast pulling Two! – Give way all! – Hit her up lively there! – All together now! – Steady! Ste-a-dy!" Then the great mossy hump was swimming so close to us I could have reached over and touched it; and bobbing some fifty fathoms astern, with drawn, anxious faces, trailed the other two boats, mere puppets in the drama. Suddenly we heard the sharp suck of the lance, then a hoarse, "Vast pulling! stern all! stern all!" We obeyed just in time! Under us the great tail lifted with a crash, and we canted off and nearly floundered. I had barely got my oar back in place when the whale broke water again, and with an exhaust like the bellow of a bull, cut across our bows. Instantly the drawn lines trailing behind him to the other boats slipped over our blades with a deadly grip, and began to creep up the looms of our oars. The boat listed and the water rose to the gun-wale. We struggled vainly to liberate ourselves. Tony tried to swing off, but we were being carried broadside with such force that the steering-oar was of no avail. "Cut the line!" yelled Mr. Hicks.

All this while the fast boats were tearing down on us, yet it seemed as if they would never realize our predicament and slacken line. I saw the man with his knife poised for a second jab; then there was a violent concussion, and a shooting sense of pain in the back of my head. A distorted vision loomed before me with threatening steel held aloft; then all was oblivion. Just in the nick of time the others had slackened line, but not before a mass of fouled gear had created considerable damage. When I came to, we were floating tranquilly on an even keel. Alfred, our stroke, was emptying a bucket of sea water over me. The other boats were clustered about, and the lifeless whale was drifting quietly up to windward. Far in the distance the Sunbeam's canvas caught the golden rays of the setting sun, and in the beauty and serenity of the scene it was difficult to conceive of the stir and passion which so recently had swayed us. |

|

Notes.

Clifford Warren Ashley (December 18, 1881 – September 18, 1947) was an American artist, author, sailor, and knot expert. . . . .

Ashley had both a knowledge of and interest in sperm whaling due to his upbringing in New Bedford. In 1904 he was commissioned by Harper's Monthly Magazine to write and illustrate a two-part article on whaling. This project necessitated him becoming even more familiar with the topic. To this end he set sail aboard the bark Sunbeam for six weeks, beginning in August of that year. During the voyage he witnessed the hunt and killing of three whales. Upon publication, the master of the Sunbeam praised the articles, stating, "I think it is the best whale story I ever read ... The illustrations are so true to life that even the Old Barnacles here cannot find fault with them." . . . .

Ashley is perhaps most famous for The Ashley Book of Knots (1944), an encyclopedic reference manual with directions for and illustrations of nearly two thousand knots.[1] He was the first author to publish several knots, including what are now called Ashley's stopper knot and Ashley's bend. Ashley also wrote The Yankee Whaler (1926) and The Whaleships of New Bedford (1929), studies of sperm whaling in New England in the late 18th century and early 19th century. |

|

Source.

Clifford Warren Ashley.

This transcription was made from the volume at Google Books.

Last updated by Tom Tyler, Denver, CO, USA, May 20, 2025

|

|